15/01/2026

Vaginal health

Vaginal Health

A balanced vaginal flora, healthy mucous membranes, and a stable pH level together form a finely tuned protective system that is sensitive to internal and external influences. Stress, hormonal changes, an unbalanced diet, and micronutrient deficiencies can disrupt this balance—with consequences that many women are familiar with. Understanding how the vaginal flora interacts allows you to do much to maintain its natural balance.

Your Vaginal Flora – A Sensitive Ecosystem

A healthy vaginal flora is the result of a finely balanced equilibrium of microorganisms, mucous membrane, and pH level. The slightly acidic pH level between 3.8 and 4.5 is one of the most important protective factors for the vagina. It creates an environment in which beneficial bacteria thrive, while unwanted germs are kept in check.Ultimately, the vaginal flora – also known as the vaginal microbiome – is a microbial ecosystem in which each strain of bacteria, like instruments in an orchestra, has its own role. Lactic acid bacteria play a central role: They produce lactic acid and other metabolic products that maintain the vaginal pH level in the acidic range. Lactobacilli play a key role in this process.

Lactobacilli as Guardians of Vaginal Health

Lactobacilli – also known as Döderlein bacteria – dominate the vaginal microbiome in our latitudes, comprising around 70%, and play a crucial role in its stability. Within this group, Lactobacillus crispatus is the most prevalent, making up 48%. [1]

- They convert glycogen and other carbohydrates into lactic acid, thus stabilizing the acidic vaginal environment.

- Some strains produce hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which inhibits unwanted germs and counteracts biofilm formation.

- Lactobacilli compete with other (undesirable) bacteria and can suppress them.

The gut as a reservoir for vaginal flora

Lactic acid bacteria ingested orally not only influence the gut microbiome – the vaginal flora also benefits from them. The gut is increasingly recognized as an important reservoir for lactobacilli, which contribute to the natural colonization of the vagina.

This also explains why locally administered products based on lactic acid or probiotic bacteria usually do not produce a lasting effect. A stable balance requires an intact microbial reservoir in the gut. Therefore, it is crucial to include the gut in the treatment.

Exactly how bacteria travel from the gut to the vagina is not yet fully understood. However, it is certain that the gut significantly influences the vaginal microbiome. Lactobacilli such as L. rhamnosus, ingested orally, can positively affect the microbiome in both the gut and the vagina. Besides the direct route through the gut to the anus, with subsequent smear infection due to improper anal hygiene, the direct passage of bacteria from the intestinal lumen into the abdominal cavity is also a possibility. There, the viable bacteria drip into the rectum (the deepest part of the abdominal cavity) and from there drain via the fallopian tubes and the uterine cavity into the vagina.

This is the basis for the variable vaginal discharge observed in some women, which can change, for example, depending on their current diet.

In the 1980s, at Kiel University, we called heavy discharge: "The bowel is crying!"

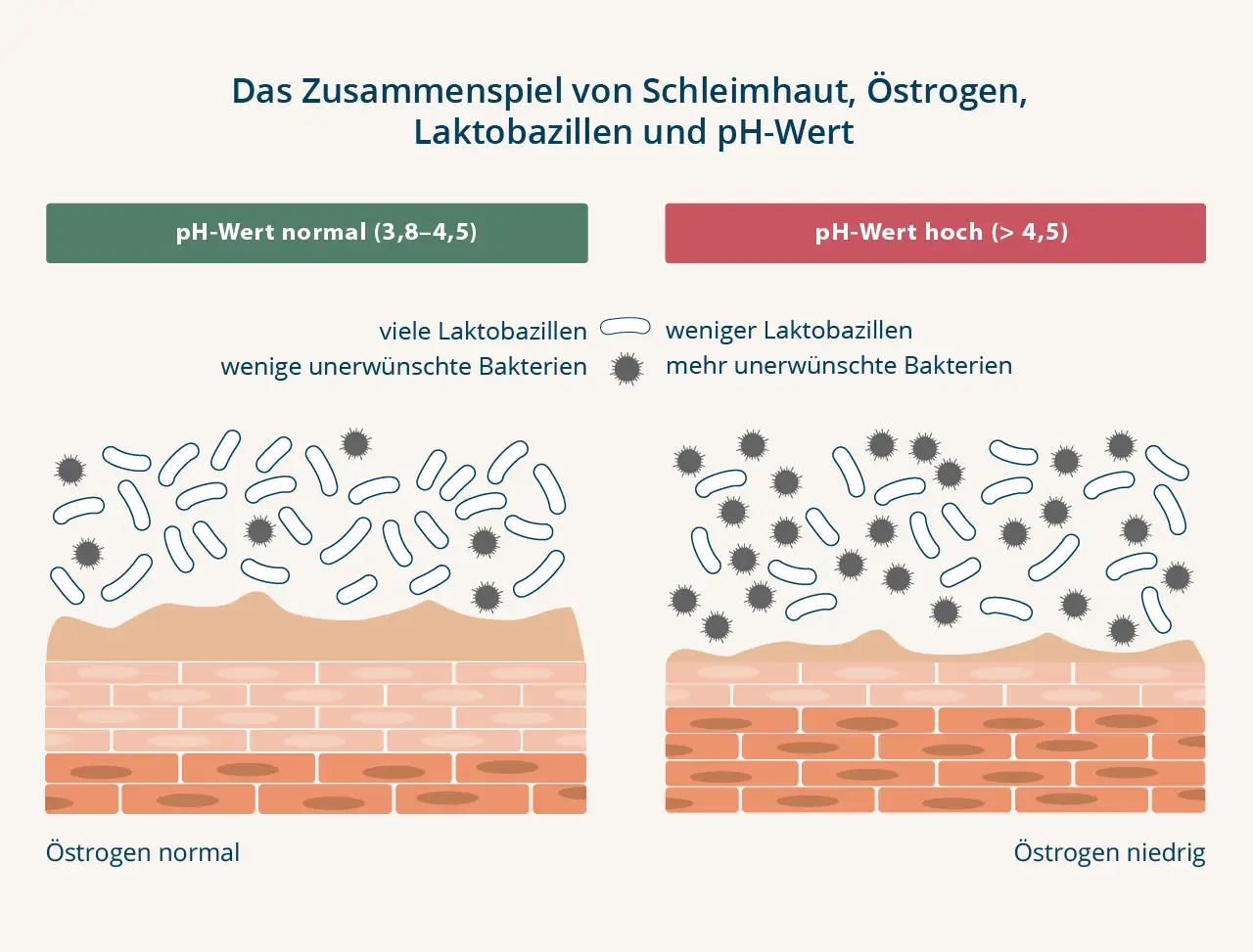

The vaginal mucosa – more than just a barrier

The most important energy source for lactobacilli is glycogen, which is produced in the vaginal mucosa under the influence of the hormone estrogen. As estrogen levels decrease, glycogen production declines. The result: fewer lactobacilli, less lactic acid. This also raises the pH level, making it easier for unwanted germs to proliferate.

Is everything in balance?

Antibiotics, shower gels, smoking, stress, and hormonal changes—such as those caused by birth control pills or menopause—can alter the vaginal microbiome. This often leads to a decrease in lactobacilli and an increase in pH.

Semen and menstrual blood are alkaline. With the rise in pH, the vagina's natural acidic environment is compromised, making it easier for unwanted bacteria to thrive.

An unpleasant odor, irritation, or simply an unusual sensation in the intimate area can indicate a disruption of the vaginal balance. In such cases, supplemental support may be beneficial.

Femininity in Flux – Hormonal Influences

The composition of the vaginal flora naturally changes throughout life. Hormonal fluctuations – especially in estrogen levels – influence the structure of the vaginal mucosa and the vaginal flora.

Even in the womb and during the first weeks of life, the foundation is laid.. An important step is vaginal birth, during which the child swallows numerous maternal vaginal bacteria. Through breast milk, the child receives further bacteria and some estrogen, which stimulates the maturation of the vaginal mucosa and lowers the vaginal pH to about 5 for a few weeks.

During childhood, the vaginal pH is almost neutral (around pH 7), the mucosa is thin, and the proportion of lactobacilli is low.

With puberty, estrogen levels rise, and the vaginal mucosa now produces more glycogen – this provides the lactobacilli with more nutrients and allows them to multiply more effectively. Lactobacilli, which are predominant in a healthy diet, keep the pH level low and thus make an important contribution to vaginal health.

During the fertile years, this environment remains largely stable. Hormonal fluctuations cause slight variations throughout the menstrual cycle: shortly before ovulation, the number of lactobacilli is highest and the pH level is lowest. During menstruation, the slightly alkaline menstrual blood (pH 7.2–7.4) causes the pH level to rise. This is why some women are somewhat more susceptible to infections during this phase.

With menopause, estrogen levels gradually decline. The vaginal lining thins, glycogen levels decrease, and the pH level rises. During this phase, the number of lactobacilli can decrease, making the vaginal environment more sensitive to external influences.

Nutrition and lifestyle

A balanced diet, adequate hydration, and a healthy lifestyle can naturally support vaginal flora.

Specifically, this means:

- Mucous membranes thrive in moist environments – so drink plenty of water.

- Consume plenty of unsaturated fatty acids from fish, nuts, organic flaxseed oil, and cold-pressed olive oil.

- When it comes to sugar, less is more. High sugar consumption can promote the growth of unwanted bacteria.

- Avoid food additives such as colorings and preservatives, as they can irritate the mucous membranes throughout the body.

- Organic is the better choice because organic foods are produced naturally, are subject to stricter production guidelines, and contain fewer pesticide residues, etc.

- A gut-healthy diet forms the basis for a well-functioning gut – and we need this for nutrient absorption, the body's own defenses, and as a reservoir of bacteria for the vaginal flora.

- For a comfortable feeling in the intimate area, proper micronutrient intake is also important. This includes, in particular:

- Biotin, vitamins A, B2, and B3 for the mucous membranes*

- Vitamins B2, C, and E, manganese, selenium, and zinc to protect cells from free radicals**

- Vitamins B5 and B6 for hormonal balance***

- Folate, vitamins A, B6, B12, C, and D, as well as selenium and zinc for the immune system.****

6 tips for vaginal well-being

Conclusion

* Biotin, vitamins A, B2, and B3 contribute to the maintenance of normal mucous membranes.

** Vitamins B2, C, and E, manganese, selenium, and zinc contribute to the protection of cells from oxidative stress.

*** Vitamin B5 contributes to the normal synthesis and metabolism of steroid hormones. Vitamin B6 contributes to the regulation of hormonal activity.

**** Folate, vitamins A, B6, B12, C, and D, selenium, and zinc contribute to the normal function of the immune system.

References

[2] Petricevic L, et al.: Characterisation of the oral, vaginal and rectal Lactobacillus flora in healthy pregnant and postmenopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012, 160, 1: 93–99 .